Everyone loves a good intubation on an otherwise long and dreary resus shift. You’re at the head of the bed, totally boss, giving commands to your attending to ‘pass me the tube’, and it feels great when that cuff passes through the cords. As you get more practiced, even difficult intubations are a welcome challenge…as long as you can intubate successfully. As we all know, a lot of things can go wrong during a tube, and once you’ve experienced a situation with a serious complication or failed airway you won’t want to be back there again.

Most residents are taught a number of tricks to make this process easier — sniffing position, standing back from the bed, having adjuncts like video and a bougie available, as well as an LMA for those difficult to bag patients, and a scalpel in your pocket (that you hope you never have to use).

Here’s a new item for your bag of tricks: back-up head-elevated positioning (BUHE), otherwise known as semi-fowler’s position. We more often discuss this maneuver in the context of GI bleeders or patients in severe respiratory distress because it helps reduce the risk of aspiration and supports the mechanics of breathing. But wait, we don’t want any of our patients to aspirate or become hypoxic, do we? The two trials discussed below provide some evidence that this position helps both to 1) decrease the risk of adverse events during intubation and 2) improve laryngeal exposure for easier tube placement.

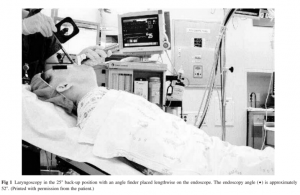

First of all, how do we do this? Easy: elevate (or lower) the head of the bed to a semi-recumbent position immediately before you intubate. The trial regarding adverse events used >30 degrees as their definition. Be careful, because you’ll have to put the rest of the bed lower than you’re used to in order to get a good view. Don’t forget to use sheets to get a good sniffing position.

Khandelwal et al. (2016) examined retrospective data from the University of Washington in Seattle. They chart-reviewed 528 patients intubated outside the OR (i.e. ICU or similar setting) by the anesthesia team. All initial attempts were by DL, with video used only as a rescue device. The primary endpoint was a composite of intubation-related complications: difficult intubation [<3 attempts or prolonged intubation], hypoxemia, esophageal intubation, or aspiration. They found that an intubation-related complication occurred in 76 of 336 (22.6%) patients when supine, and 18 of 192 (9.3%) of patients when managed upright. When adjusted for BMI and a pre-assessed difficult airway score, this works out to an odds ratio of 0.41 for complications – that’s pretty good!

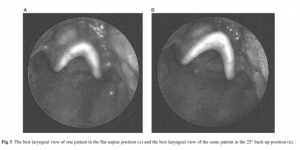

A separate trial by Lee et al. (2007) examined the upright position in the controlled setting of the OR, performing laryngoscopy on the same patients in both positions, using video imaging to rate the views obtained in a blinded manner. They found that even at 25 degrees of inclination, an average of ~25% more vocal cord exposure was obtained in the head up view (below). This could potentially dramatically improve a grade III or grade IV view.

So next time you’re getting ready for that intubation, try keeping your (patient’s) head up. You might get a look from your attending, but you’re more likely to walk away looking as happy as the inspiration for today’s title: (note, the author does not condone Andy Grammer).

References

Khandelwal et al. Head-elevated Patient Positioning Decreases Complications of Emergent Tracheal Intubation in the Ward and Intensive Care Unit. Anesthesia and Analgesia. Apr 2016.

Lee et al. Laryngeal exposure during laryngoscopy is better in the 25 degree back-up position than in the supine position. British Journal of Anaesthesia. July 2007.