By Lara Silverman MD/MPH, Emergency Medicine PGY3

October 9, 2022

Intro:

Let’s talk about the B-side.

The B-side can be a hard and scary place to work for many reasons. Not only are patients agitated or altered, but they also have a high likelihood of trauma and often have chronic disease at baseline. I once had an elderly patient with an alcohol of 324 who was able to fully range his displaced femoral neck fracture (with ease!). I have definitely had at least one patient with a large subdural on their CTH, which we ordered for “an abrasion.” And every now and then, someone with known alcohol use disorder will develop variceal bleeding and need immediate intubation and upgrade to cardiac.

It is also important to note that though a patient might seem like presumed intox, this is not always the reason for altered mental status. I once had a patient with an alcohol of zero and a creatinine of seven. He wasn’t intoxicated, he was uremic. So how do we know who to “watch and wait” and who to go all out on?

Special considerations in patients who use alcohol:

At baseline, individuals who have used alcohol are at increased risk of having many disease processes. Acutely, discoordination and a decreased pain response predisposes individuals to trauma, with lack of insight to their injuries. This puts them at risk for further injury (and makes a history and physical exam much less reliable). Additionally, always consider hypoglycemia as contributing to altered mental status, as alcohol has the potential to increase insulin release and patients often have decreased overall caloric intake.

Alcohol also starts to weaken the immune system with only moderate use. Alcohol damages mucosal barriers in both the GI tract and lungs. It also causes lymphocyte and monocyte dysfunction and predisposes individuals to sepsis and various cancers.

As we know, alcohol is metabolized primarily by the liver and chronic alcohol use leads to liver disease. Patients with alcoholic liver disease have impaired synthesis of clotting factors, platelets, and albumin; impaired glucose management; and impaired blood detoxification. This leads to thrombocytopenia, coagulopathies, edema, ascites, and the list goes on. Importantly, liver disease can lead to portal hypertension, which can in turn lead to the formation of esophageal varices. These varices can result in deadly hemorrhage with minimal warning.

TL;DR: The Algorithm:

About the algorithm:

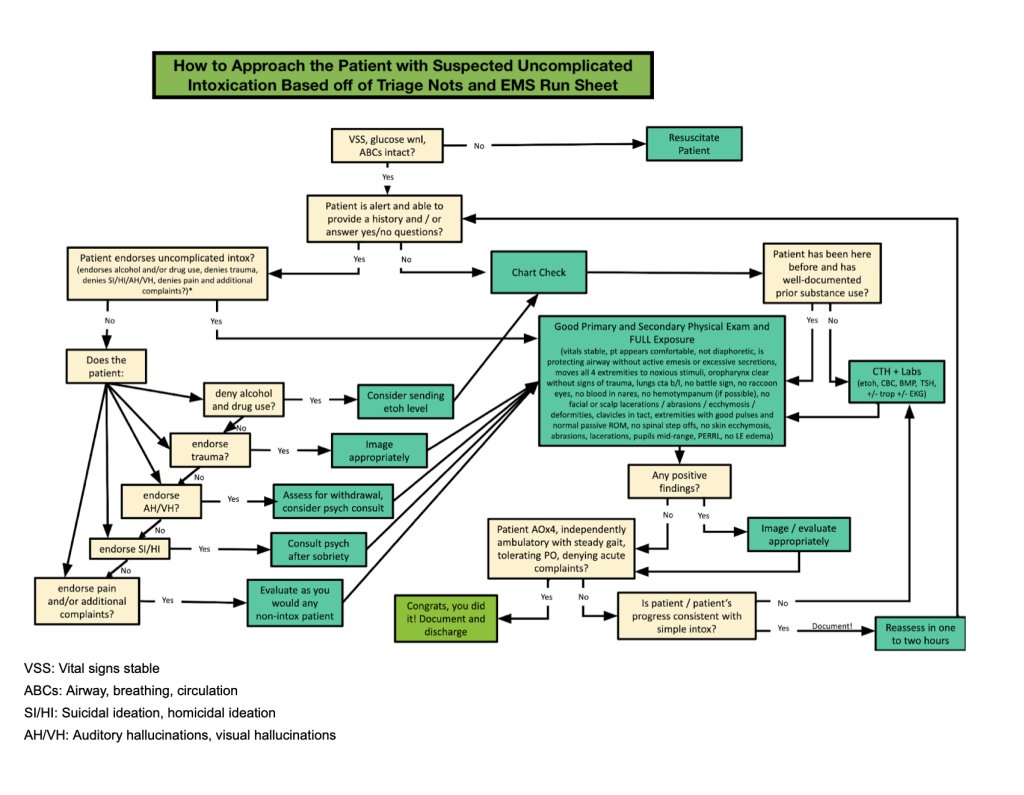

As with most things in medicine, having an algorithm to fall back on helps us make sure we are not missing something important. My personal algorithm for the patient with presumed intox is above. I will describe it briefly.

As with any patient, if the vitals are unstable, ABCs are compromised, or the patient is dangerously hypoglycemic, stop and resuscitate the patient. Assuming that is all normal, glance at the triage notes and look for an EMS run sheet (in media, if present). Note anything out of the ordinary (ie, suicidal/homicidal ideation, trauma, shortness of breath, strange context of the patient’s encounter with EMS). Pay attention to these abnormalities when getting the history and physical.

Go to assess the patient. If your patient is able to talk but with limited participation, run through a checklist of items: make sure the patient endorses alcohol (or drugs), denies suicidal or homicidal ideation (SI/HI), denies trauma, and denies any other complaints. In my experience, patients are forthcoming about alcohol ingestion. If they are altered and deny alcohol (especially if they are not well known to the hospital system), this is concerning. Have a low threshold to order an alcohol level and/or screening labs + head CT. If there are any other positive findings, address those appropriately.

After the interview, perform a very thorough physical exam. This can be fast, but it must be complete. Look at ALL skin including the feet, check pulses, press on all bones, make sure all 4 extremities move to noxious stimuli, do a really good HENT exam. Basically, think of this person as a trauma patient. Do a good primary and secondary survey just like in any trauma. If there are any positive findings, especially on the head / face, have a low threshold for imaging.

After that initial history and physical exam, reassess the patient roughly every hour. This is a LOT of reassessment (12 times over a 12 hour shift, in theory), so just do it every time you walk past this patient. Be fast but thorough. Check to make sure the patient is still breathing with ABCs intact. Make sure no new battle sign or ecchymosis at the flank has developed. Make sure all four extremities move. And importantly, make sure the patient is moving the direction you expect them to– talking slightly more, requiring slightly less (ob)noxious stimuli, etc. Document as you go and at any point, have a low threshold for labs and/or CTH.

A special consideration in this algorithm is the patient who denies drugs or alcohol, or who is not able to provide any history and is not known to the hospital. Often agitated patients are sedated in triage and by the time the primary provider evaluates them, the patient is unable to participate in an interview. Even if a triage note says a patient endorsed and smelled of alcohol, if a patient is not well-documented within the hospital system and is unable to tell you themselves that they ingested alcohol or used drugs, this patient deserves at least screening labs and a head CT.

You will know your patient is ready for discharge when they are “clinically stable.” Note the use of the word “clinically,” as a patient who drinks daily might be “clinically stable” when their alcohol is still reasonably high. A patient is ready for discharge when he/she is AOx4 (person, place, time, circumstance), can hold a conversation with minimal prompting, denies additional complaints, has a benign physical re-exam, and most importantly, can tolerate PO and walk with independent steady gait. (As a side note, as Dr. Lugassi pointed out, in NYC we don’t have to worry as much about our patients driving home with an alcohol level still over the legal limit. However, if you practice somewhere like Baltimore, where I basically couldn’t survive without my car, be cognizant that getting an alcohol level might be tied to a specific length of stay.)

Side note: Get the CTH

As Dr. Grossman pointed out, this study from 2014 at NYU/Bellevue followed 51 patients who were identified as patients with high etoh utilization. The results were impressive:

- They had over 1600 imaging studies (>30/pt on average!)

- It cost $192,000 (relatively low, all things considered)

- Over that timeframe, 39% of subjects had moderate/severe brain injury, most of those with ICH

- 8 of them died during the trial

Dot Phrases:

Picking up patients with presumed intoxication is a big responsibility, but having a quick algorithm and a good dot phrase can really help. Here are my dot phrases, though be extremely careful when using any dot phrase, to be sure you are not documenting pieces of a history or physical you did not perform. It is often helpful to think of dot phrases as much as a “checklist” to make sure you followed through with your algorithm as a tool to aid in documentation.

.history: [use after you’ve documented the basics – age, gender, PMH, info from triage / EMS run sheet]

Patient is alert to (***physical stimuli/voice) and able to answer yes/no to questions. Endoses alcohol (***denies/endorses drug) use, denies trauma, denies SI/HI/AH/VH, denies pain, no additional complaints.

.HENT: [typed in in the HENT PE click boxes]

Airway intact without excessive secretions, emesis, or blood. Pupils mid-range and PERRL. No battle sign, no racoon eyes, no blood in nares, no nasal septal hematoma, no blood or discharge from ears. No crepitus or bony deformities on palpation of facial bones. No abrasions, lacerations, ecchymosis to face or neck. Head normocephalic without hematoma, laceration, abrasion, blood, or signs of trauma.

.MSK: [typed into the MSK PE click boxes]

Moving all 4 extremities (***spontaneously / to noxious stimuli), no ecchymosis, lacerations, abrasions, or bony deformities on extremities. Spine without step offs. No ecchymosis or crepitus on torso or flank. Lower extremities without notable edema or erythema.

.A&P: [use after your one-liner for patient with simple intox]

Patient presenting with likely acute uncomplicated intox. (***Intox complicated by trauma/psychiatric concern/etc). No psychiatric concerns, concerns of trauma, or concerns of complicating underlying pathology at this time. Physical exam unremarkable. Below threshold for additional labs or imaging. Will continue to reassess for sobriety or developing pathology.

-Acute uncomplicated etoh intox

-Continue to reassess for sobriety

-Dispo likely home

.reassess: [include an additional few words about the evaluation]

Patient alert to progressively less stimuli, as expected given acute intoxication. Will continue to reassess.

.discharge: [use this the final reassessment note prior to discharge]

On reassessment, patient alert and oriented to person, place, and time. Endorses alcohol (***/drug) use prior to arrival and (***voices recollection of history as reported by triage/ems). Independently ambulatory with steady gait, tolerating PO, voicing no additional pain or acute complaints. Physical exam without any new ecchymosis, no tenderness to palpation on spine, bony extremities, or facial bones. VSS. Patient endorses ready for discharge, discharged to home.