Is Your Cat Rabid or Just a Psychopath?

Written by Erena Weathers

First and foremost, rabies due to domesticated dogs in the US is pretty much eradicated. From 1960 to 2018, 127 human rabies cases were reported in the US, and a quarter were due to dog bites in returning travelers, and 70% were due to bats. From 2009-2018, there were 25 reported cases of human rabies, and only two of those people survived. The majority of reported rabid animals are wildlife, followed by cats, dogs, and then cattle and horses.

Rabies is caused by neurotropic viruses in the Rhabdoviridae family, genus Lyssavirus. Lyssaviruses prefer neural tissue and spread via peripheral nerves to the central nervous system. They replicate near the peripheral nerves and then move retrograde towards the CNS 50-100mm a day. This leads to an incubation period of 1-3 months to possible years from exposure.

You have encephalitic and paralytic types of infection. Both are preceded by a prodrome of general viral infection. Encephalitic rabies is characterized by fever, hydrophobia, pharyngeal spasms, and hyperactivity subsiding to paralysis, coma, and death. Paralytic rabies is an ascending paralysis that can mimic Guillain-Barre. Either way, you’re probably going to die if you get to either of these stages. Mainstay treatment is supportive care in an ICU, but mortality is outrageously high and there is no standard therapy. People try Rabies Ig and Vaccine with some help and other antivirals, but more than likely the rabid patient is going to die in a brutal manner. This is why we harp on prevention.

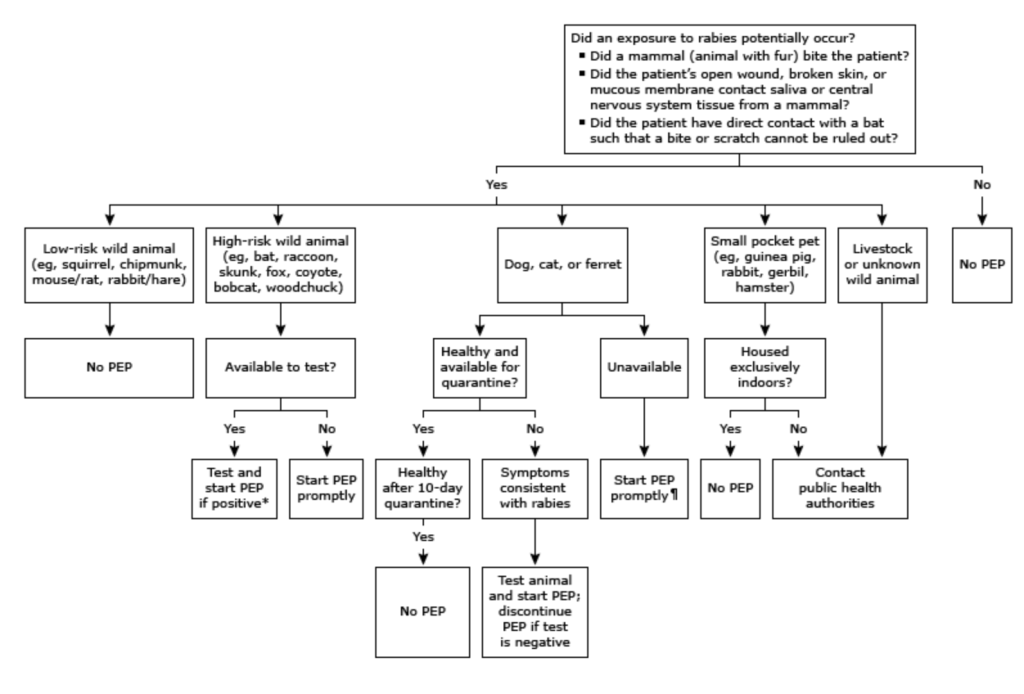

So let’s prevent our patients from becoming rabid. First off, wash the wound vigorously and then move on to therapy. You can take a look at the attached charts, but to sum it up, if bitten by a high-risk animal (wildlife esp bats, or unknown status dog/cat) inject rabies immunoglobulin near the site and start the vaccine series. If the patient is immunocompromised, an additional dose is recommended on day 28. You will see this on Rosh and/or inservice about what days to administer the vaccine.

Per ACIP and the CDC, you should be injecting RIG around the wound as much as possible, and then if there is any leftover, inject into the contralateral deltoid/thigh of where you administered the vaccine. Ex. bite in the right hand, RIG in the right deltoid, and vaccine in the left deltoid or thigh.

Per the WHO, you only need to administer RIG near the bite, and if you have any left over, don’t need to inject the rest into the deltoid/thigh.

Per both, if you don’t have enough RIG to properly infiltrate near the bite, then you can dilute with sterile saline.

Onto antibiotics for bites.

More important in cat bites than dog bites due to the little kitty dagger teeth and ~5% dog bites become infected. There are high risk bites in which antibiotics are recommended: injuries requiring surgical repair, wounds on the hand, face, or genitals, close proximity to a bone or joint (even a prosthetic one), near areas of vascular/lymphatic compromise, immunocompromised patients, deep puncture wounds (kitty dagger teeth bites), or associated crush injury. Your main choice of antibiotic will be Amoxicillin-clavulunate 875/125 BID (augmentin) for 7 days, you are trying to cover Pasteurella multocida. If none of these are present, then it can be a discussion about prophylaxis with the patient, and shared decision making with a two day wound check.

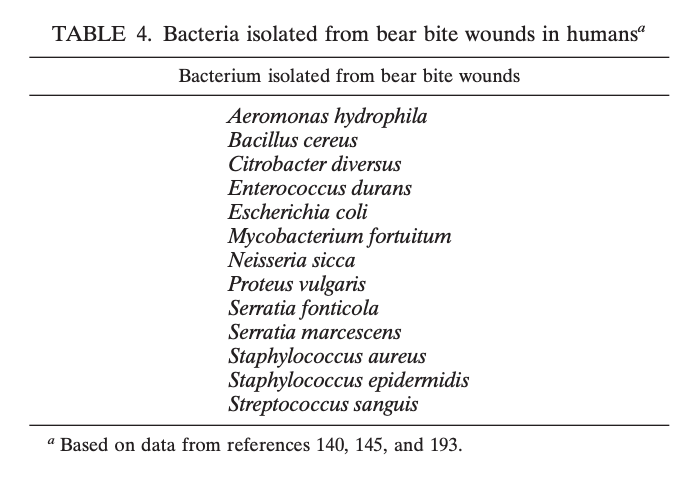

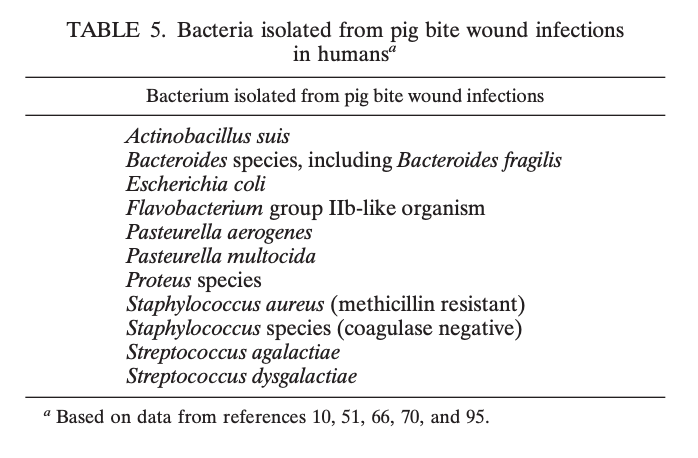

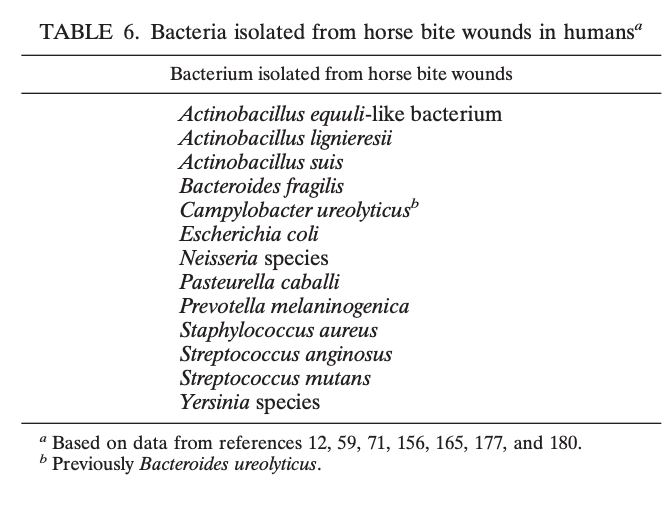

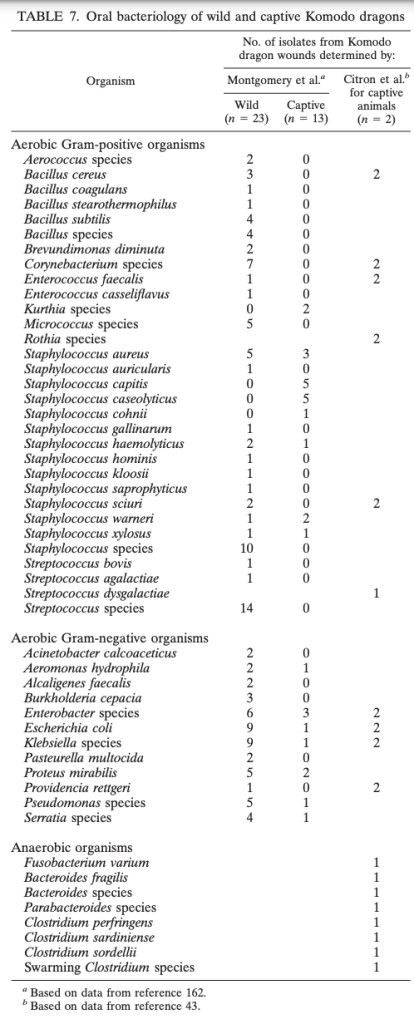

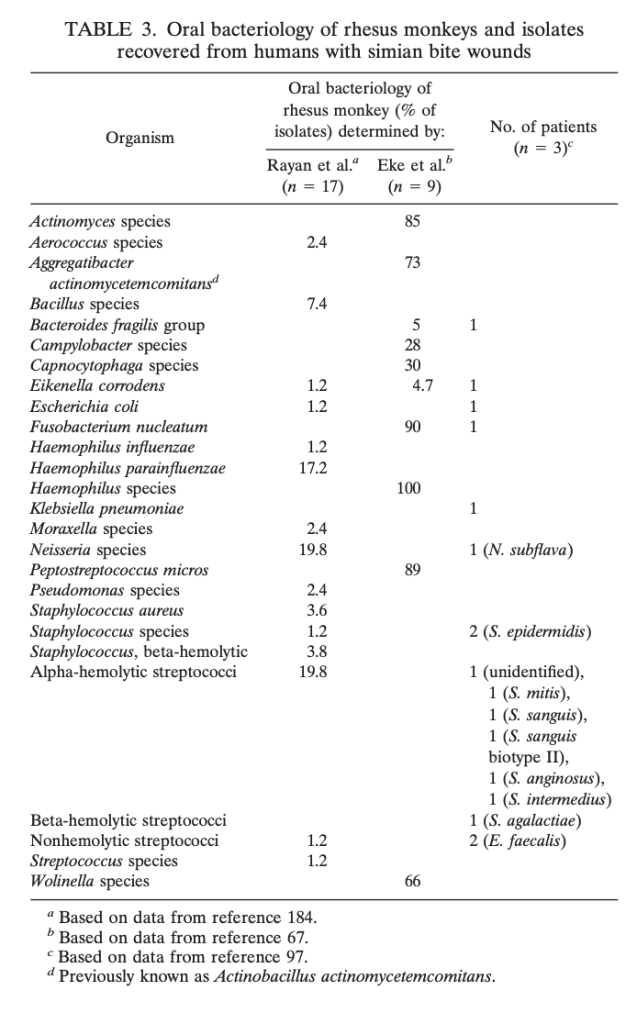

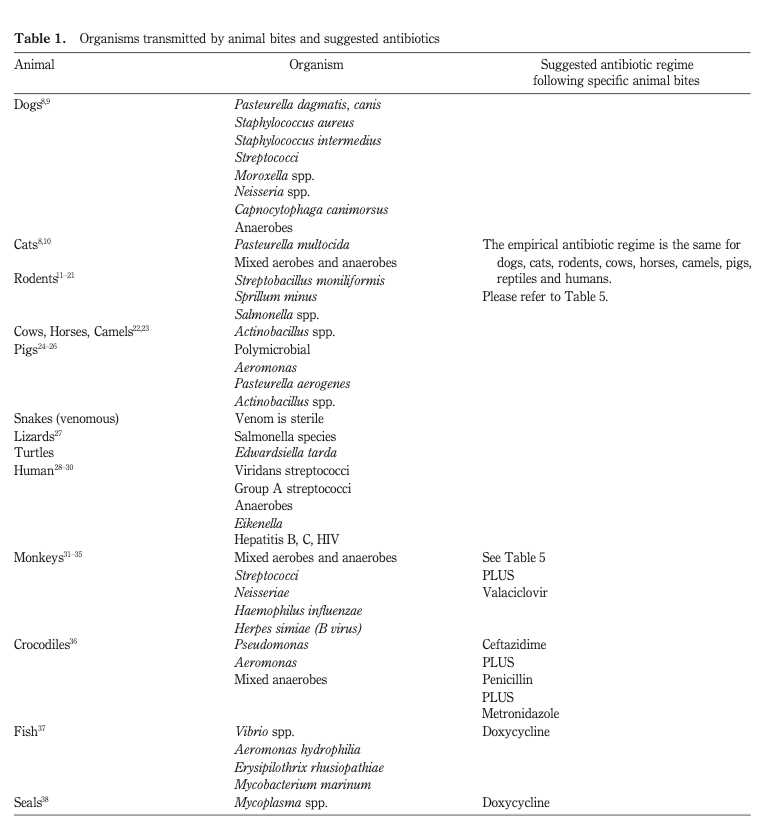

Here are some tables with rare infections due to bites from other animals. (Not pictured, Vibrio from a shark bite). Good luck making it to the end and avoiding manbearpighorsekomododragon attacks:

If you made it this far here are some other options for antibiotics for other pesky creatures:

References

DeMaria Jr, Alfred, and Catherine M. Brown. “Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of rabies.” UpToDate (2018).

https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/index.html

Human Rabies. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/human_rabies.html

World Health Organization. “Frequently asked questions about rabies for clinicians. 2018.”

DeMaria, A. “Rabies immune globulin and vaccine.” Up to Date. (2014).

Baddour, Larry M., Marvin Harper, and A. B. Wolfson. “Animal bites (dogs, cats, and other animals): evaluation and management.” UpToDate (2019).

Dendle, Claire, and David Looke. “Animal bites: an update for management with a focus on infections.” Emergency Medicine Australasia 20.6 (2008): 458-467.

Abrahamian, Fredrick M., and Ellie JC Goldstein. “Microbiology of animal bite wound infections.” Clinical microbiology reviews 24.2 (2011): 231-246.