A quick search of sinaiem.org for the keyword measles brings up a solitary post from 2015, and it’s not actually about measles. With all the attention that measles has been getting in the news recently, now seems like a great time to revisit measles as a disease process, and go a little deeper than just the three c’s (although we’ll mention that too).

Starting with some history… The first account of measles was published in the 9th century. It wasn’t until 1757 that Francis Home, scottish physician, was able to show that measles was caused by some agent in the blood of infected people. In 1912, the US started tracking and monitoring measles in earnest. In the decade following, there was an estimated 6000 measles-related death a year. Measles was once so wide spread that nearly all children contracted the disease prior to age 15. The year prior to the release of the measles vaccine saw 3-4 million new cases, 500 deaths, 48,000 hospitalizations, and over 1000 cases of encephalitis (1). In 1963, John Enders and colleagues succeeded in isolating the virus, and then creating a vaccine. In 1968, an improved and even weaker measles vaccine, this is the same vaccine we still use today, although it is usually paired with the vaccines for rubella, mumps, and more recently varicella. Introduction of the vaccine saw incidence rates fall dramatically, however an outbreak in 1989 among vaccinated school-aged children prompted recommendation for a second dose of MMR vaccine for all children. After widespread adoption of a second MMR dose, the rate of measles declined even further. By 2000, measles was declared to be eliminated from the U.S, but thanks to false narratives about being linked with autism, it didn’t take. Which more or less brings us to the present day, where measles is once again a threat – and we providers have to be vigilant in our surveillance. Thus our need for a refresher, which begins now.

What is it?

The measles virus (MeV) is a single-stranded, negativesense RNA virus in the genus Morbillivirus of the family Paramyxoviridae. It is an extremely contagious airborne pathogen, can be transmitted via small aerosolized particles, and can stay suspended in the air for several hours.

What are the signs and symptoms?

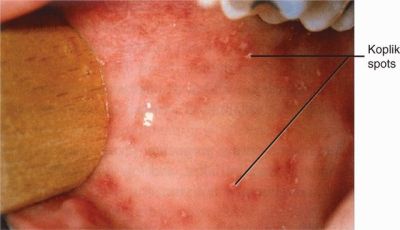

The symptoms of measles do not manifest until seven to 14 days after a person is infected. Symptoms include cough, coryza (rhinorrhea), conjunctivitis (the 3 C’s) + High fever. Two or three days after symptoms begin, tiny white spots (Koplik spots) may appear inside the mouth (seen here:)

Three to five days after symptoms begin, a rash breaks out. It begins as flat red spots that appear on the face at the hairline and spread downward to the neck, trunk, arms, legs, and feet. Small raised bumps may also appear on top of the flat red spots. The spots may become joined together as they spread from the head to the rest of the body (seen here:)

Who is at risk of contracting measles?

Unvaccinated persons of any age, pregnant women, immunocompromised patients, and infants.

How is it diagnosed?

Measles is usually a clinical diagnosis, however there are laboratory methods of confirming your suspicions. The most commonly used method for laboratory confirmation is detection of IgM, usually by enzyme immunoassay, in serum samples collected at first contact with a suspected case.

How is it managed?

Treatment of uncomplicated measles cases typically involves supportive care, including antipyretics, antitussives, hydration and/or environmental controls (like humidification/cooling). Currently, no antiviral therapies with demonstrated clinical effectiveness exist for treating measles, although limited case reports suggest that intravenous or aerosolized ribavirin might provide some benefit in severe disease (3). Most complications are secondary bacterial infection, which can be managed with antibiotics. Severe complications include respiratory failure, acute encephalitis, and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (which may not develop until several years after initial infection.) Given the supportive nature of care, the majority of management of measles is based around isolation, containment, early vaccination, and providing post exposure prophylaxis to those at risk who have come in to contact with an infected person.

Post Exposure Prophylaxis?

To potentially provide protection or modify the clinical course of disease among susceptible persons, either administer MMR vaccine within 72 hours of initial measles exposure, or immunoglobulin (IG) within six days of exposure. Do not administer MMR vaccine and IG simultaneously, as this practice invalidates the vaccine.

Takeaways (TLDR):

Measles is/are back. Ask about vaccination status. Report new cases to the CDC. The 3C’s + High fever proceed the rash. Rash spreads from face downwards. It is a clinical diagnosis. Management is supportive. PEP exists.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

- https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/transmission.html

- Forni, A., L., Schluger, N., W. & Roberts, R. B. Severe measles pneumonitis in adults: evaluation of clinical characteristics and therapy with intravenous ribavirin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19, 454–462 (1994).

- Rota PA, Moss WJ, Takeda M, de Swart RL, Thompson KM, Goodson JL. 2016. Measles. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2:16049.DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.49, PMID: 27411684