Whether it’s asthma, a U.R.I., or post nasal drip as the cause, cough is a common enough complaint encountered by emergency physicians everywhere. Of course you must always rule out the dangerous causes of cough (PNA, Measles, PE, Heart failure, CHF, lung cancer PVCs ) but once thats done, you still have to treat the patient. Given it’s ubiquitousness, you’d imagine that there’d be a myriad of effective ways to treat a cough.

Alas, I’m certain one day in the low acuity area of your ED, during December, would certainly make you scrutinize the use of the word effective. I’ve heard of everything being used from guaifenesin to albuterol, from tessalon perles to hycodan, but effective isn’t the word I’d use to describe these treatments. Usually, I default to telling a patient it’ll all clear up in a week or so, (kicking the can down the road and hoping this becomes the problem of their primary care doc). But is there something that can be used in the ED for “effective relief?”

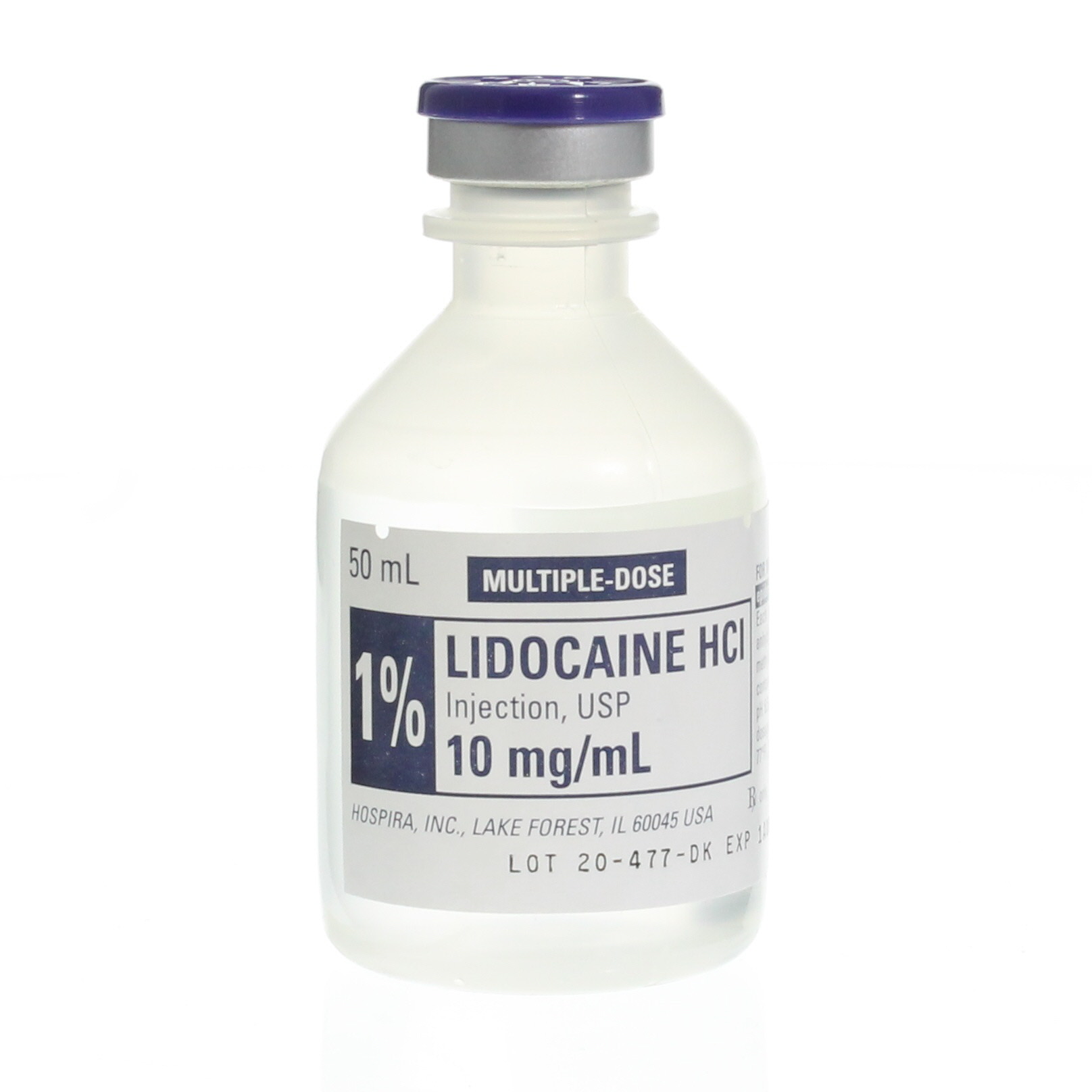

How about Lidocaine?

Yes, that the stuff.

Lidocaine is a local anesthetic that is used in a whole host of procedures. In the ED, we know its uses well, but here’’s one you may not have heard of before.

Nebulized lidocaine for cough relief. Nebulized lidocaine is often used in bronchoscopy to increase comfort of patient and allow for further visualization of the airway. There is some literature (mostly case reports), that show although nebulized lidocaine is not first-line therapy in intractable cough and asthma, it may provide an alternative treatment option in patients who cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to other treatments (1,2).

The main concern over lidocaine is surrounding it’s toxicity. Concentrations of serum lidocaine over 5 mg/L can lead to lightheadedness, tremors, hallucinations, and even cardiac arrest (3.)

Also, patients suffering from hepatic disease should be monitored closely because of decreased drug metabolism and elimination rates.

So here’s how to do it:

Start with 100 and 200 mg of liquid lidocaine (about 5 mL of 4% or 10mL of 2%) topical lidocaine solution (equaling approximately 200 mg) and to nebulize it, squirt it into the nebulizer chamber, connect to wall o2 at 10 LPM, and have the patient breathe it in. This is believed to numb the airway and stop bronchospasm, thus stopping the cough. Be sure to warn the patient that it doesn’t taste great and it can sometimes cause a slight burning sensation. Patients should experience relief within 10 minutes if successful. Hopefully it works, if not, there’s always the PMD follow up.

Here’s to having one more tool in the arsenal.

______________________________________________________________

Work Cited:

- Slaton, Thomas & Mbathi (2013) Slaton RM, Thomas RH, Mbathi JW. Evidence for therapeutic uses of nebulized lidocaine in the treatment of intractable cough and asthma. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2013;47:578–585. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R573

- Shirk MB, Donahue KR, Shirvani J. Unlabeled uses of nebulized medications. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;65:1704–1716.

- Langmack, Esther L. et al. Serum Lidocaine Concentrations in Asthmatics Undergoing Research Bronchoscopy. CHEST , Volume 117 , Issue 4 , 1055 – 1060

- More Emergency ‘MacGyver’ Tips for Physicians. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/912367